My Wanda Gág Study

I collected 13 things I learned from Wanda Gág’s life and work here. But there is so much good stuff out there that I wanted one place to keep track of everything.

I’ve organized it like a Q&A for easy perusing. You’ll also find a list of her work and a bibliography of the resources I’ve found so far.

Her life and work

What was she like?

5 foot 3 inch tall

Black hair and black-brown eyes

Petite and always looked younger than her age

Often wore a black leather coat

Simultaneously social (some called her flirtatious) and reclusive

Saw everything —experiences, relationships, sex, etc.— through the lens of what would help or hurt her life’s work

Strong professional drive which served her well when she had to support her family of seven after her parents died

One person described her as “a strange mixture of innocence and wickedness.”

Journaled consistently her entire life

Her friend Howard Cook said:

She was a charming dark haired girl with sparkling eyes, a richly sensuous person slight of figure but aesthetically dynamic and humorous, endowed with a rich talent which expressed in her own rhythmic imaginative sense, her love of life and the surging vitality and activity of all growing things, a world of magic passion in which even the most commonplace objects seemed to possess an inner organic sense of aspiring. Her early death was a great loss to the American art scene for I have never known another artist who had the distinctly unique vision she possessed. I am deeply grateful for having been touched by her life.

—

To never miss a learn-from-the-greats study, subscribe to my newsletter here.

—

What was her childhood like?

Wanda Hazen Gág was born on March 11, 1893 in New Ulm, Minnesota—a small community settled by middle European immigrants.

“I was born in this country, but often feel as though I had spent my early years in Europe. My father was born in Bohemia, as were my mother’s parents. My birthplace—New Ulm, Minnesota—was settled by Middle Europeans, and I grew up in an atmosphere of Old World customs and legends, of Bavarian and Bohemian folk songs, of German Märchen and Turnverein activities. I spoke no English until I went to school.”

Her parents Anton Gag and Lissi Biebl (Elizabeth) immigrated to the United States from Bohemia and Germany. They both prioritized creativity in their work and home life. Anton supported his family by selling his oil paintings, photography, and decorative paintings on walls in homes and churches. Lissi designed and sewed costumes and clothing for her kids. She also worked as Anton’s photography assistant and became a talented photographer herself. She loved infusing art into life’s details like making valentines made of lace and forming the extra bread dough into little books that the kids would open and spread butter down the middle.

They encouraged Wanda and her six siblings (Stella, Dehli, Howard, Asta, Thusnelda, and Flavia) to draw, listen to music, and play dress-up. Anton and Lissi would stop working to look at the kids’ drawings or answer their questions. The family often drew together at dinner.

“I spent my earliest years in the serene belief that drawing and painting, like eating and sleeping, belonged to the universal and inevitable things of life.”

She hung out a lot with her dad in his attic studio and loved “the silent serious happiness in the air.” He taught her illustration principles and techniques. She loved writing and illustrating her own stories.

What inspired her to become an artist?

When she was 15, her dad passed away from occupational tuberculosis on May 22, 1908. His last words to her were, “What Papa couldn’t do, Wanda will have to finish.”

“All my life I have wished there were some way of getting across to my father some of the sympathy and appreciation which was denied him in his lifetime. All I could think of doing was to fulfill his wish…to the best of my ability, hoping that in some way it would even things up.”

She kept a note from him on her desk: "diligent observation, study, and practice.”

One example of his wisdom to her was: “An artist . . . whatever he does and produces, must always observe and gather and retain new impressions, teach himself and let himself be taught, and success will not be lacking.”

Her life motto also came from him: “draw to live, live to draw.”

How did she get her start as an illustrator?

After her father passed away, her mother’s health declined and she was confined to bed. Her youngest child was only one at the time.

She describes that time as, “a jumble of housework, hungry children, endless woodchopping…and adolescent sentimental moods and a yearning for oysters and butter….there was rarely enough food.”

As Wanda had to help take care of the younger kids and do a lot of the cooking and cleaning, her community pressured her to quit school and get a job to support her family. But instead she committed to putting all of her siblings through high school by selling her stories and drawings to magazines and patrons.

“I have a right to go on drawing. I will not be a clerk. And we are all going through school.”

She felt judged for her family’s poverty, her desire to finish school, and her dreams of making art:

How much did I belong to myself? To what extent had I the right to ignore myself—not the physical part that walked around and worked, but that fiery thing inside which was always trying to get out and which made me draw so furiously?

As a freshman, she had made $100+ from her art and her original drawings and stories were published in the Junior Journal, a Minneapolis newspaper dedicated to young people’s work. She discovered her father’s old financial ledger, and decided to use it to continue keeping track of what she earned from her art. This also became her journal.

In it she documented the money she made from her art, where it went (often to support the family), and the poems and drawings she was consistently submitting. Here is one poem she wrote in 1908 called “The Snowstorm.”

“I go to bed with my candle-light.

Outside the world is solemn and whitie,

And quietly, softly, hushed and slow,

Come the pretty, white little flakes of snow.

And leaving the world so calm and so white,

I creep to bed in the peaceful night.

In the morning when I get up, Oh ho!

The world is full of the drifting snow!

The little red house way down by the hills,

Is drifted with snow to its window sills.

I meet the world in the ealry morn,

In a jolly, frollicky, wild snowstorm.

She worked incredibly hard on top of all of her family responsibilities. Here is an entry from her diary on November 2, 1908 when she was 15 years old:

“Today is ironing day and ironing night too it seems…Fern Fischer was here yesterday and she said that somebody told her I don’t do anything but read and draw. I guess so! I wonder if washing dishes, sweeping about 6 times a day, picking up things the baby and howard throw around are reading. And I’ve never heard of taking care of babies, combing little sisters, cleaning bed rooms & attics as being classed as drawing! I wonder what else people will say about me.”

And a week later:

“I wasn’t good today. I read too much and didn’t work enough. But really I wish I hadn’t been so bad.”

That December, she and her siblings celebrated the Feast of St. Barbara by breaking a small branch off a fruit tree and making a silent wish before placing it in a vase of water. The idea was if the branch bloomed before Christmas, the wish would come true. She often wished to finish high school and study art:

“Dreamt about school last night. I could almost cry myself sick sometimes to think that so many girls who have the opportunity of going thru High School just hate school and look upon it as hard work; while I have to be afraid any time that I may have to stop school before I know it.”

Despite her determination, she also doubted herself sometimes:

“O dear, what have I done? Next to nothing. Compare my drawings to those of Jessie W. Smith, J.M. Flagg, H.C. Christy and all the rest. What are they? Why, they’re noughts, zeros, nothing, against them. I’ve often though of this but never wrote it down. I wonder whether I”m making any progress at all, and whether I’ll be clever enough to earn much money, at least enough to make us all comfortable. I wish I could see and talk with…my favorite artists.”

How did she go to art school despite her family’s financial challenges?

In 1912, Wanda finished high school then taught at a rural school for a year to support her family.

She still wanted to do art but didn’t have the money. But she kept submitting to things and eventually a few patrons who saw her talent offered to pay for art school. To her patron, she wrote:

“I marvel at how you were able to find me through my rather inadequate little poems and illustrations, but you did—and as I re-read your letters I was deeply touched by them. I was so bewildered, so timid about acknowledging Wanda Gág, and so very much alone, aesthetically. Your letters were like a substantial, but forming-like latticework for my groping young tendrils to hang on. With your apt and intense way of putting things, you showed me the way to myself, and with your tactful praise you gave me confidence in that self. In short, you made me feel much more at home with Wanda Gág than I had been since the death of my father…you were the one who first supplied me with the Springboards from which I could leap into the land where I really belonged. And I do thank you very much for that.”

She went to St. Paul School of Art and the Minneapolis School of Art. She would return every summer to help her family. Her next oldest sisters supported the family by teaching.

What was art school like for her?

Rigorous

Often struggled between the rigidity of instruction and her need for inspiration.

Life without a drawing mood is miserable, miserable, miserable…I am trying to entice, to lure, and to recapture it, but of course it's all in vain. Drawing moods, delicious tyrants as they are when they let me draw, are cruelly tyrannical when they don't let me see things so that I want to draw them, and they cannot be brought by human aid.

I am blamed for not working when I’m not inspired…I see first and then I do…When I draw, I draw. When I don’t draw, I am studying character or other things and I’m sure the time is not wasted.

Struggled because her creative process was different than what her teachers required.

I always feel that the best way to study art is to study other things with it…It seems to me it cannot be wrong to read good poetry an entire morning if you happen to be particularly receptive in that respect, because when you are poetically receptive, you see so much of life behind the world.

Like her life drawing teacher told her she had to block the entire figure first in four lines, but she liked blocking things in her mind so her lines would feel more “spontaenous.”

I don’t give two cents how other people work. Just because every one else works one way, is just the reason why I must work another. An imitation never gets far and, what is worse, no one who is an imitation can be himself.

In 1917, she received a scholarship to the prestigious Art Students League in New York with her friend (and eventual lover) Adolph Dehn

What was her personal life like during art school?

Explore exhibits and galleries with friends, expanded social circle including lots of different types of artists

Met once a week with other free-thinkers to discuss “love, humanity, justice and similar things”

Friendships kept her going when she wanted to quit school

What was her first big break in the book world?

1917: editor commissioned her first children’s book illustration, A Child’s Book of Folk-Lore-Mechanics of Written English by Jean Sherwood Rankin

Received praise from publishers and started seeing children’s books seriously as a career path

How did she support herself and her family?

In 1917, her mom passed away. The community wanted to send her younger siblings to foster homes and orphanages. But Gág sold the house and moved her family to Minneapolis instead. She gave each child a job to keep the household going and worked in New York to send money home to her family.

She continued to make connections in the commercial art, magazine, and gallery world.

All along the way her family struggled. Her male friends were going off to war. There were political conflicts at her college. She was always worried.

She moved into a costume designer’s studio and slept on a cot to save money while she built up freelance commercial work. She didn’t like it but it paid the bills.

I am happy to get as much work as I am getting, but my bigger and temporarily squelched self is becoming very importunate these days and demands of me all sorts of sacrifices for its satisfaction and expression. It is not exactly a pleasant feeling. It doesn't show a great deal just now, but I am relentlessly ambitious, and it makes me ill to have to do this other, and to see other people go on ahead expressing themselves, while I have to stay temporarily in the background.

Had to take odd jobs like decorating lampshades or commercial fashion work (hated it the most).

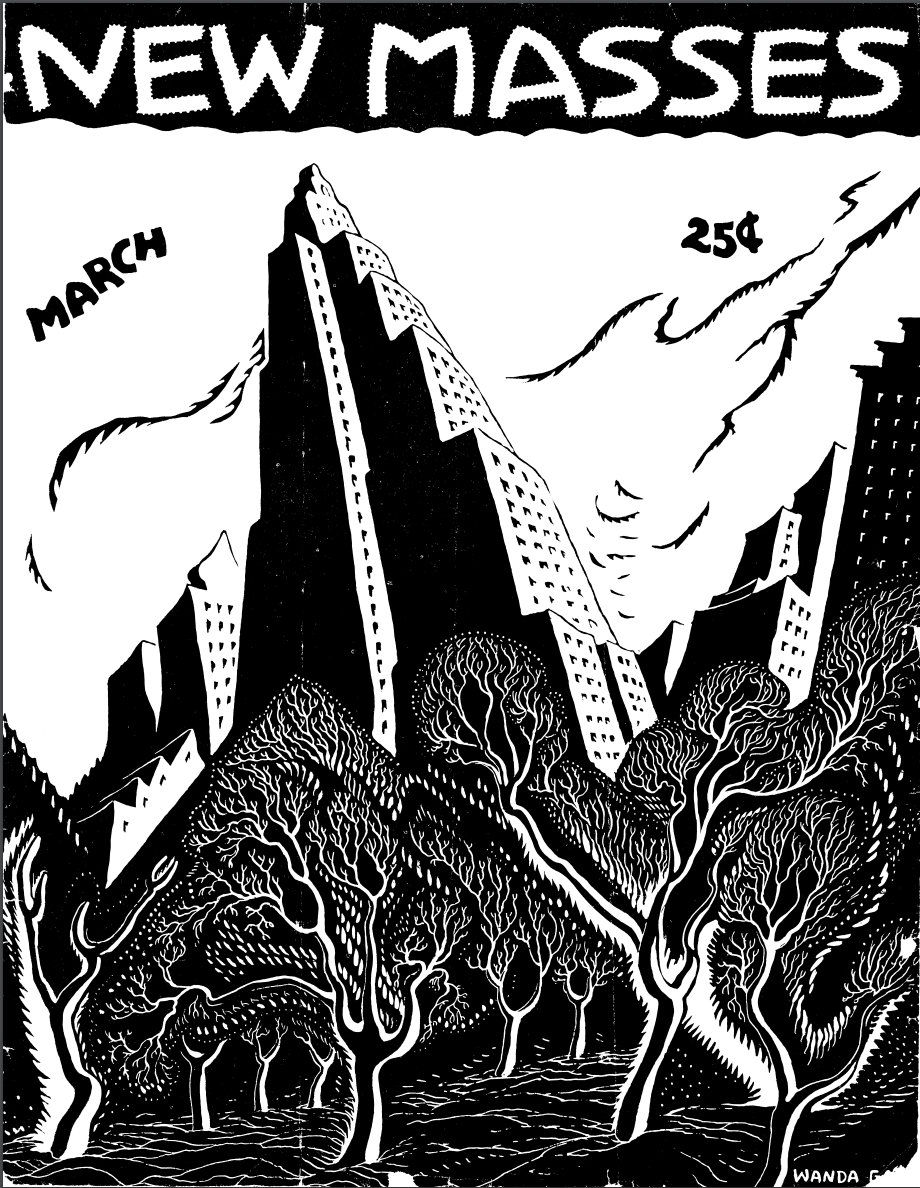

Made over 100 lithographs between 1920 and 1928 — was well known as a printmaker

Continued working as a freelancer for magazines and producing other commercial work but the demand for social commentary and political cartoons was growing which Gág saw as formulaic and condescending.

Struggled because she hated the work and wanted to honor her own creative voice but needed to provide for her family. Also struggled with the “artificiality, the “glare,” the “high unnatural key of things,” and the materialism she experienced in New York:

"I do not want to live in the restless, hectic, busy-busy life for which Americans are noted. I want to sort of ramble through life — not lazily, for I must be active to be happy. I want to read and study and work hard and live, but I do not want always to feel myself rushing along in pursuit of money."

Called this her “hideous period” when she was “unable to do anything worth while” — also broke up with Dehn which pushed her into “the only time” in her life that she “struck bottom”

Spent the holidays in Connecticut and determined she needed a return to nature for her work.

How did nature influence her work?

Left NY to rent a home in Connecticut — friends, lovers, and family visited while she studied nature, “trying to extract from them the marvelous inexhaustible secrets of their existence.”

The country was lovely. I had decided to draw if I could possibly force myself to do so. By the third day I despaired of being able to accomplish anything. But I took my drawing material and sneaked off to the woods. But nothing would come. Everything seemed too subtle for me to grasp and put down. I lay face downward on last year's leaves and basked in the warm sun. And I meditated. It helped. Here I was among Nature's rich rhythms. Nothing but her little stirrings and murmurings were to be heard. People were far away, abstract. I knew I could not always think so, but for the time being I felt that self-expression, art, nature's fertile and elemental measures were the things my life was to be swayed by, and that human beings were but feeble forces compared to these.

I tried to make myself consider what it was I was really drawing at. I have had some difficulty in doing this lately, due to almost a year's abstinence from unhampered self-expression.

The result of all this was that I regained my artistic bearings sufficiently to make two drawings. Bad ones, of course, but they were a beginning. The next day I made six drawings, the one after that 3, and the last morning I made 3 more. Some are not totally bad.

Partner Earle Humphreys and Gág’s siblings did chores while she worked

Submitted and was featured in exhibits and galleries. Sold lithographs, children’s boxes, and crossword puzzles.

It made me happy to think that I had been able to get money for the things I really liked to do. That doesn’t happen often enough.

Lost the Connecticut rental so she and Earle moved to rural New Jersey. Rented an old three-acre farm they called Tumble Timbers.

Struggled to make work without money for art supplies, so asked an art gallery to help her sell her drawings — they did and took a smaller commission than normal.

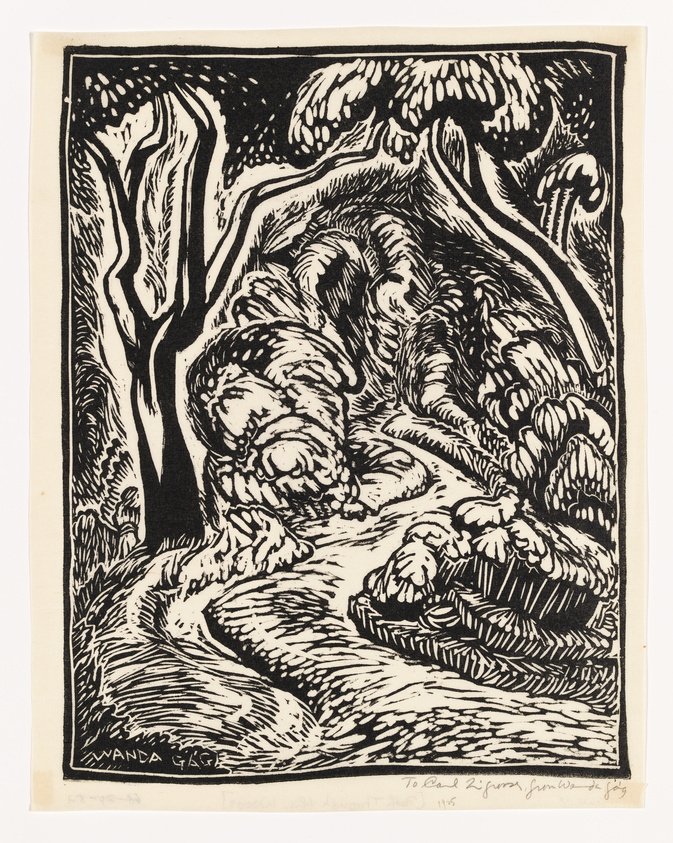

First solo exhibition at age 33 in 1926 at Carl Zigrosser's Weyhe Gallery in New York. Successful financially and critically.

The joy I get out of drawing overwhelms me. This feeling has been heightened by several forms of appreciation, which have come to me recently. The fact that I have tangible proof of my things giving pleasure to several people gives me a greater pleasure in doing more of it. It gives me greater confidence in my view point, and the result is probably a greater strength and spontaneity in my drawings.

Able to financially support all seven siblings graduating high school

Could finally leave commercial art

Now that she could dedicate all of her focus to her passions, what did she discover?

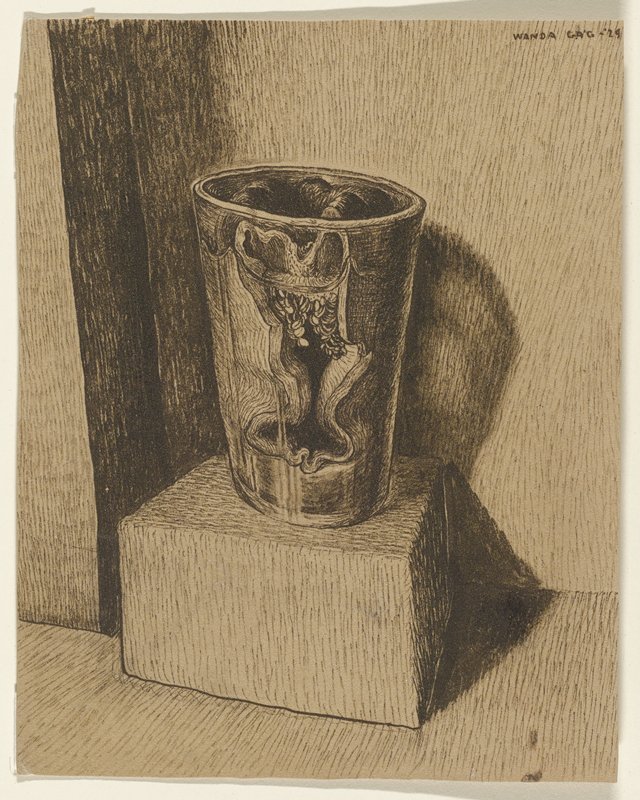

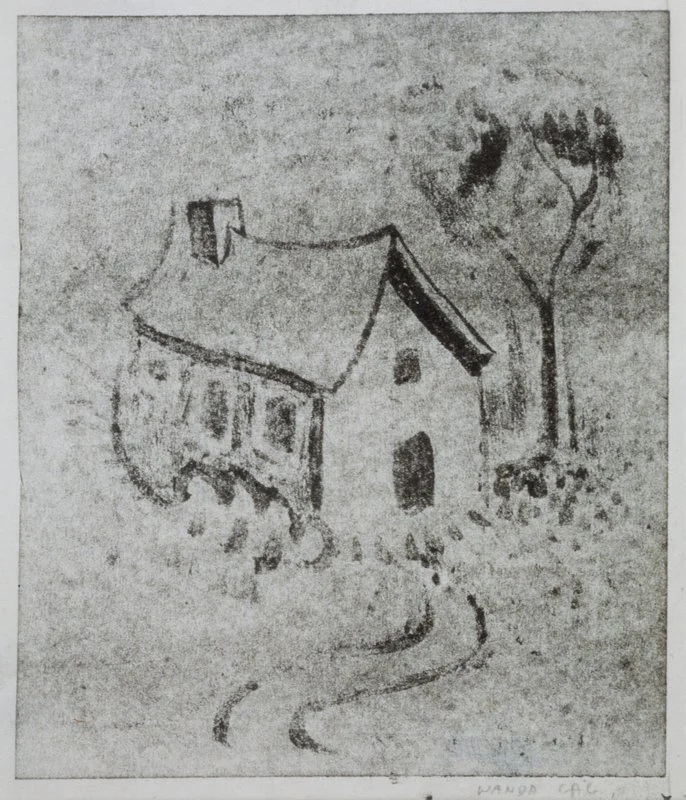

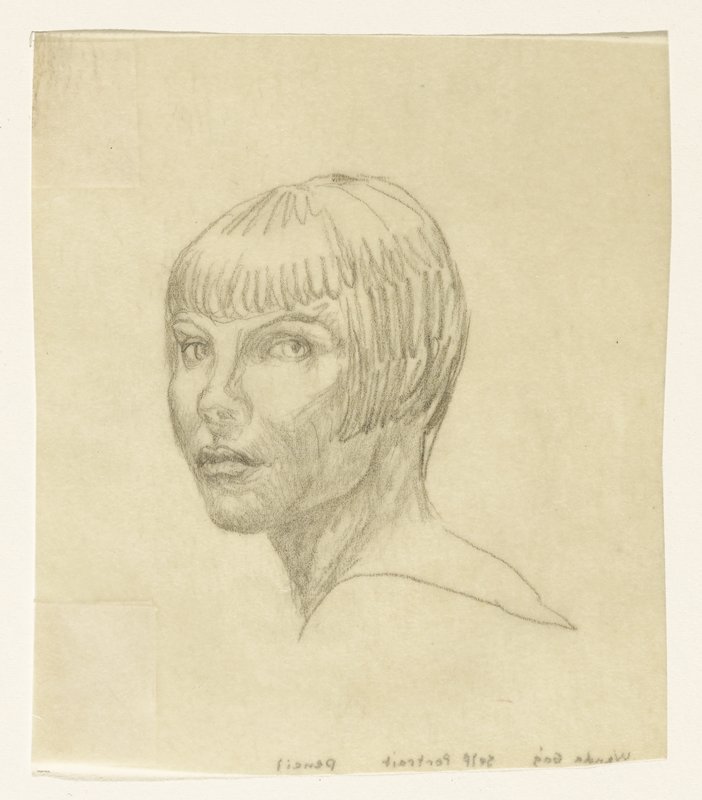

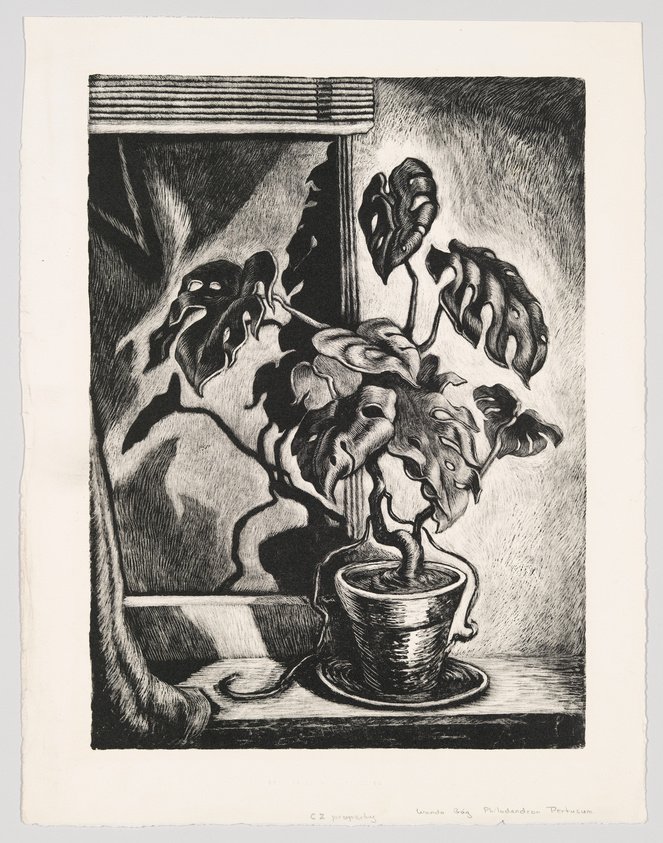

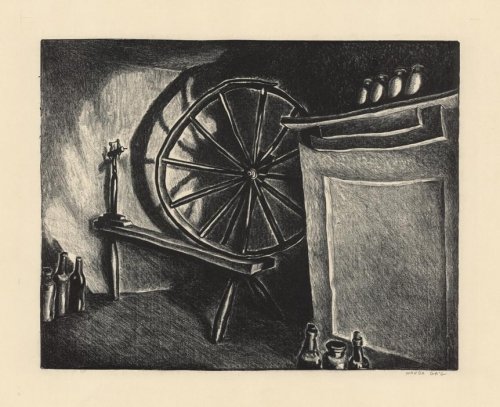

Throughout her life, she participated in multiple exhibits and gallery shows. Her speciality was making ordinary things come alive on the page using distortions and other techniques.

A still life is never still to me.

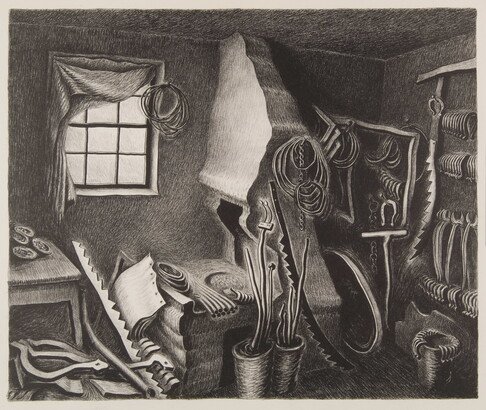

The following gallery is a collection of some of her work from 1915-1947 from the Minneapolis Institute of Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and the Old Print Shop.

Explored her artistic voice; focused on “seeing with a free-er eye”

Wanted to capture the spirit of nature in her work.

There is a seeming intelligence of inanimate things, a unique grace and power as if this tree has meant a great deal to the land for so many years."'

Often took her art supplies with her outside “in quest of the hill form principle.”

“I want to show the volume of atmosphere, its essential form as related to (or rather produced by) the object it surrounds.”

Drew by lamplight in the evenings

Sometimes her sisters were her models.

Signature sandpaper — experimented with zinc plates, using a watercolor brush wash to make solid shapes or outlines and the lithographic crayon to build up values.

I am anxious to do my very best on them—I want them to look as tho they had grown, and not as tho they had been ‘turned out.’

Eventually, experimentation guided her to Millions of Cats.

How did Millions of Cats get published, and how did it impact the publishing industry?

1920: submitted half-finished manuscript about cats to a New York publisher and gotten rejected (most likely because she was an unknown artist at the time.)

1926: Successful solo show that gave her connections and critical acclaim in fine art for watercolors and print-making — editor named Ernestine Evans at Coward-McCann publishing firm noticed. Impressed with Gág’s whimsy, heart, childlike honesty.

1928: Millions of Cats was published and immediately became a classic.

Didn’t talk down to her audience. Brought European folktale sensibility to a didactic field.

Believed children are capable and observant — do not need to be shielded from reality.

Certainly children are fascinated by stories concerning the modern miracles of science, and why shouldn't they be? But why shouldn't they also be interested in other kinds of stories? In fact, I believe it is just the modern children who need [fairy tales], since their lives are already over-balanced on the side of steel and stone and machinery…"

Hit with reviews and readers. Sold 15,000 copies within a year.

Oldest book that has never gone out of print

Influenced all the picture books that came after it because Gág treated both the text and illustrations as elements of composition.

Cared a lot about the quality of her books. Brother Howard hand-lettered the text because Gág didn’t like what the publishers had provided. Spent days at the printing shop fighting for the highest quality print job.

This review from the famous librarian Anne Carroll Moore says it all:

“Is the story based on an old folk tale?” I asked Wanda Gag.

She shook her head. ”No it isn’t a folk tale,” she said. “I invented it, pictures and all, for some children in Connecticut who were always clamoring for stories. The way of telling it may have been influenced by the Marchen I heard as a child. They were the stories I know best. What we have known and felt in childhood stays with us,” she added, with a quick, rhythmical movement of her whole being.

No cloying reminiscent from Wanda Gag. She’s alive to the tips of her toes in a living present. I shall always see her moving with confidence, her headlight the most piercing dark eyes I have ever met.

“Cats are very hard to draw,” I ventured.”

“Don’t I know it,” replied Wanda Gag. “I had to live with two of them to do millions.”

There you have the secret of Wand Gag’s power. She trusted neither her inward nor her outward eye alone—each sustains and supports the other.

What inspired her work?

Her father. Her dad was a huge creative force in her life — before and after he died. Her life motto: “Draw to live, live to draw.”

Nature. She focused on what she called her three passions: art, sex, and growing things.

I am a great surprise to myself.

I am not ashamed of myself.

Art is my greatest passion, but at the present, just plain everyday passion is at the head of everything.

Old trees and her garden of vegetables and flowers (her favorites were philodendrons) were huge inspirations for her. She loved walking barefoot in the woods and swimming in lakes, and she would often set off to “do battle with the hills” with a sketchbook.

I feel so damn civilized when I get into their wild, reckless midst that I have a great contempt for my city-self. It's then that I want to tear off all my clothes and lie among the grasses, lean my naked self against the trees or enjoy the contact of my breasts against hard stone. Or else I want to run-fast and senselessly, rejoicing in the physical facts of sun, breeze and muscular action. But that isn't all. I also like to sit and watch the forms and rhythms of the clouds and the essence-form of trees and hills, and I like to let my eye create compositions wherever I direct it, with curved and diagonal force-lines, inter-relation of spaces and forms, all complete.

Other creatives. Transcendentalist writers, especially Henry David Thoreau, also inspired her philosophy for life and art. Her friend gave her a copy of Adolf Just's Return to Nature, which influenced the way she built her home. She also pushed herself to achieve new artistic heights by studying Van Gogh and Cezanne.

“Everything I looked at cried out to be captured and set down on paper. It mattered little whether I looked at a landscape or a junk heap, a cat or a flower or a week, my Sears-Roebuck bed, or my bare kitchen—each thing had a personality and life of its own, and all arranged themselves in ready-made composition about me.

Her family. In 1929, she returned to her childhood home to promote her picture book The Funny Thing. She spent five weeks visiting her maternal family in New Ulm and collected objects that she would use in her work. Her whole extended family was creative. Growing up, her aunts sang songs and told stories and taught her family how to cook and sew. Her uncle Frank inspired her as an artist as he crafted writing desks, cabinets, guitars, and other beautiful objects. And her uncle Josie drew, painted with watercolor, and built birdhouses and toys. After many years apart from her family, this trip provided an important reconnection with her roots.

She wanted her art to unify "all the helpless fringes and frayed edges of our groping lives."

Other influences. Folklore, Bohemian folk songs, zither music, German fairytales Illustrated works of Goethe, Schiller, and Heine. Van Gogh. Listened to Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony and read Dostoevski while canning cherries to relax.

What was her creative process like?

She drew things by visualizing the finished composition in her mind and then she would try to match that vision as close as possible on the page. Instead of blocking in the big picture, she would fully complete a section of the composition at a time, paying special attention to the relationship between objects and the space around them. She preferred to capture everything “in principle” — essence over accuracy.

More and more I realize the value and necessity of searching for essence at the expense of all else. Once you get that thought through your mind you will not be bothered much by cleverness of technique, style or too great a facility in handling.

The Forge.

She often described her fascinating process in great detail — like this is how she made “The Forge.”

This lithograph was done on zinc with brush-and-tusche and some crayon. Its texture consists of thousands of tiny strokes, and it took me several weeks to do it.

The subject is an old forge near Carversville, Pennsylvania. I was excited by the varied form of the tools and hand-wrought objects in it, many of which had obviously not been moved for a long time and had fallen into mellow patterns. Almost they were static elements in the picture, but not quite—the dynamic zigzag of the saws created a center of energy which seemed to me to shoot out and by its force compel the more passive forms to take part in its rhythm. I set myself the problem of controlling these forces: to keep them moving without letting them flow out of the picture, to build them up into sort of a cadence.”

From the rough, yet detailed drawing made on the spot, I went on to several more, striving each time for a more compact and compelling organization, and establishing the final values. In my work I do not rely on happy accidents; I know beforehand exactly what I want the final result to be and work consciously toward that goal. In this case, after solving all the problems to the best of my ability, I made a final drawing on tracing paper, traced its outlines on the reverse side with sanguine crayon, and transferred it to the zinc.

With the transferred lines as guides, I drew the main outlines very lightly on the zinc, using a #5 Korn lithographic pencil.

I warmed a small dish, rubbed Lemercier tusche around its inside, and added water to make a fairly dense wash. This was applied with a watercolor brush wherever crisp rich outlines or small solid masses were needed.

Next, the values were built up very gradually all over the picture with Korn lithographic crayon (#3 when the room was cool, #4 when warm).

Then came the ticklish part; heightening the darks with the tusche wash without creating a soggy black mass. This is especially risky on zinc, for, whereas such sections can be lightened up on stone by scraping, no corrections can be made on zinc. I use a dry-brush technique in such a way as to leave a faint sparkle of zinc showing through.

Finally, I like to keep the lithograph around for at least a week "for observation," and for last minute touches. Studying it by twilight or looking at it in a mirror are valuable aids in this respect.”

What did her career look like after Cats?

High demand in both the fine art and children’s book world

Work was shown at the Museum of Modern Art and the New York World’s Fair.

Continued to make children’s books and art.

“I aim to make the illustrations for children’s books as much a work of art as anything I would send to an art exhibition. I strive to make them completely accurate in relation to the text. I try to make them warmly human, imaginative, or humourous - not coldly decorative - and to make them so clear that a three-year-old can recognize the main object in them.”

1931: bought farm in rural New Jersey and built a studio called All Creation.

Made Snippy and Snappy, The ABC Book, and some Grimm fairytale translations.

Attempted an ambitious project to illustrate Walden Pond but never finished.

Royalties supporter her and her family during the Great Depression

How did she continue developing herself as an artist?

Threw away lots of sketch experiments along the way. Did master copies of Cézanne and Van Gogh to explore space and form and achieve more depth.

Put a lot of pressure on herself; especially frustrated trying to master painting (may have been tied to her father, but also felt pressure from mentor Carl Zigrosser who believed paintings would elevate her career)

I am so anxious to find myself in painting this time.

Never felt satisfied with her use of color — became muddy or felt only decorative.

Friends and family worried about the exhaustion they could see in her

Continued making lithographs

I have been working on three lithographs. With two of them I got quite daring, one might say reckless, in the use of washes, and I’m afraid I’ve spoiled them. But I felt the need of doing something drastic in order to get into a freer style, and even if they’re spoiled, I don’t mind. I will have learned something by it.

After the declaration of WWII, started writing more and more.

While I'm painting nowadays, I feel selfish to be putting down one stroke or another, while human beings are starving, being executed and being killed by millions on the battlefields; with writing, somehow this feeling is not as strong, perhaps because I feel that provided I can perfect myself in this craft, I will later be able to write some of my deepest convictions as I could not hope to do graphically or in color.

Had been writing diaries consistently her whole life and eventually published an autobiography in 1940

My diary means my life, and what’s in my life must go into it. The only way you can keep out of my diary is to keep out of my life.

What are some other fun facts about her?

She later added the accent to her last name.

Her youngest sister Flavia also became an artist and children’s book maker. She, Wanda, and one other sibling collaborated on Sue Sew-and-Sew.

Her childhood home was purchased as an official historic place. You can go visit it here.

What were her final years like?

Health began to decline — bed-ridden over long periods of time.

Hands swelled up after painting — had to wear gloves all the time (possibly from lead poisoning)

Overcome with self-doubt about her latest work

Some of the things I wrote about art made me feel that I wanted badly to draw fiercely again, smashingly; in big rich, frill-less powerful rhythms. I feel definitely that my work of recent years has not had sufficient power, and sometimes I am overcome with a certain fury because of it. I don’t know how to describe it. I want to weep tears of fury and defiance as I say, “I can do it. I still have something to say. I will do it.”

Occasionally cut out meat, coffee, and tobacco to try to restore herself.

Ultimately, at age 50, she showed the first signs of lung cancer.

Oh, I do hope everything will come out alright. I still have so much drawing and painting to do. If I can get over this I feel sure I will have it in me to draw better.

There is no pretending that I am not worried about it all, and I just don't feel like dwelling on it. Earle has been so very good and efficient and helpful and last night when he left to go to bed I said "good night darling, I love you very much." That's quite a lot for me to say—not that I didn't feel it often, but it is just part of the Gág character of understatement. He was moved and pleased and he said some endearing things too and we both had tears in our eyes.

Husband Earle stayed by her side her final two years before she passed away in 1946.

My aim is limitless. That I will never reach it I know, but I'm going to get as near there as I can. That will keep me running all the rest of my life, believe me.

Inspiring quotes

In her journals, Gág grappled with big questions about marriage, motherhood, sexism, romance, success, and more. As I read her words, I felt simultaneously grateful for the freedoms I have now and SEEN because the conflicts we grapple with today are (sadly) similar.

Here are a few relatable excerpts from her journals that I thought you might appreciate.

What did Wanda Gág say about…

Feeling simultaneously judged for your success and failure

Throughout her career, her community called her ambitions frivolous and impractical. They gossiped about the reasons why her art studies were being financed by men. She felt judged her success and also potential failure:

They expect me to make a great deal of money and, sort of along the side, to become famous. And when I want neither fame nor money…I am afraid I shall disappoint them. If I were to become a popular magazine illustrator they would undoubtedly say, ‘Wanda has made good,' whereas if I turn my art over to Life and win no fame, they will say, 'She had talent but she didn't use it in the right way.’

Feeling like you have to prove yourself just because you are a woman

Underneath all this brave generalizing, I quiver, face to face, with the horror of my life as a woman. It's a darned hard world for women to make any headway in, and I'm just dissatisfied and tenacious and rebellious enough to want to show them that there are a few women that can do something.

I am not anxious to forget that I am a woman, but I am very anxious to convince myself, if no one else, that just because I am a woman is no reason why I should be left behind a man.

Being overwhelmed by the fight

Tonight my life frightens me: I seem to see clearly just what my problem will be for some years to come, if not for always. Womanly charm and similar feminine attitudes will get one somewhere in a minor fashion. It can get one jobs, or admirers, even a patron or two perhaps.

But it cannot solve the big mess, as you know as well as I. There are some things which mean just plain fighting, and as a man has fewer things to fight, a woman to get where the man gets, has to fight just that much more, and that is what frightens me.

Mentally, I may be able to free myself from all these things, and physically to some extent, but I do realize my limitations in the latter, and I know that in this lifetime I cannot free myself absolutely from my sex. All I can do is to do the best I can.

Struggling against your social training to place others as the center of your universe rather than yourself

If I still insist that art must come first and the man second, and if I set my criterion of right and wrong by what is good or bad for my progress in this greatest passion of mine, I should try to keep myself free from such love-slavery as I have been making myself miserable with during the past year.

I must make myself the centre, and remember that the wisest thing to do is to keep myself in a position to be combined, dissolved, re-combined, re-dissolved, and so on.

I cannot help playing with the idea that possibly Life itself in its baffling complexity is however without aesthetic finality. Perhaps there is not one big Plan. Perhaps it is a chaos of separate plans—crisscrossing and scattered helter skelter all about us just as nature is. Our duty and prerogative then would be to select an inherent synthesis according to the dictates of a particular make-up, and live by that.

The pursuance of the aesthetic, and the expression of it as invested in me, is the one stable element of my life. It is the one thing I can believe in and depend upon. All else is change and confusion.

Feeling like marriage might limit your career

Gág was a feminist who shocked her New York art school friends when she declared she wouldn’t marry unless her husband ran the house while she drew.

I am not nearly ready to settle down and get married. I'd make a punk wife anyway and I just couldn't imagine myself settling on one man for life.

She constantly grappled with her views on romantic relationships. She didn’t want to get married because it would negatively impact her work, but she also didn’t want to miss out on experiences she felt were essential to her life and work.

I love because I am ready to love, I love because I need it for my work.

I wish to experience the physical in order that my mental and spiritual appreciation may be more complete and intense. I want to use it in my work. If I never marry, I have no intention of remaining a virgin. I should want to delve experimentally, if not otherwise, into that realm denied to old maids.

Worrying that having children might limit your career

She also felt she had to choose between marriage and children and her work.

In my life there could be no room for a child. I don't suppose you can appreciate what it meant for me to give up that idea…But six youngsters and no money to give them an education proportionate to their capacities seems to me to be quite enough for one lifetime. And it is always a woman's art that has a hunk of years taken out of it—while the husband, or (to be broadminded), shall we say the father, can go on comparatively uninterrupted.

Sound familiar? ;)

Having difficulty connecting with loved ones who are creatively stifled

Dear Earle, why don't you write?

It was one of the things which I hoped would be the natural consequence of our companionship, and since there have been only a few fragmentary such results I sometimes wonder whether I have really been good for him. Whenever I think of this the tears rush to my eyes. It gives me a feeling of frustration, of having fallen short of what I had hoped from myself. Next to creating myself, my greatest joy is to help others to create. It is easy to see what a really deep disappointment it is to me not to have been able to accomplish more with one who has been closer to me than anyone else. The fact that he has helped me immeasurably in this way heightens rather than alleviates my unhappiness about this matter.

Creating from a place of wonder

When I look at a group of my drawings, I sometimes feel as though I had exaggerated what I had seen. But when I am looking at nature or drawing directly from it, I feel quite helpless to draw it otherwise. It is all there, and I marvel how it happened that I could ever have doubted my vision.

There they are, the trees, enhancing each other's lines and forms by opposition, repetition or agreement. There is an intricacy, an understanding between them—perhaps rapprochement is the word—a unity of purpose, in fact such an intelligent and moving symphony that I cannot conceive of a more beautiful manifestation—or, if you will, proof—of God.

My idea of God, that is—a god which is a general, inescapable, incomprehensible principle, a god which (I mean which, not who) is everywhere and keeps its universe in magnificent order, fragments of which we are occasionally allowed to discover and enjoy and halfway understand.

To express such of these fragments as I am allowed to perceive is the only thing worth living for to me. That is my religion.

Exploring other forms of art

All this has given me a new reaction to music. I noticed it this morning, when, as I have said before, I played Schubert's Unfinished Symphony. I see a relation between color and tone, but music has never seemed so clearly allied to the color to me as it has to the form of a picture.

I feel a long note with little repetitions dropping or rising from it, and the building up of large masses to a climax is so easily perceived as to scarcely warrant its mention. Straight lines run through it, and diagonal ones. All this is not new to me. It has always been more or less a matter of two dimensions, a flat design. But today I came closer to appreciate its third dimension. For instance, it was not simply a rhythm building itself…but it grew up like a building with sound for its masonry. Is that absurd?

The sound did not simply go from left to right. It came up from all sides, not a matter of wavelengths, merely, but of volume. I think I can hear little mounds of music scattered here and there, and shapes like rolling hills. Some of its forms are rounded, some cubic, and others pyramidal.

Finding joy in the search

The search, and an occasional peep behind the scenes gives a more intense joy than any kind of reputation, except perhaps a bad one!

I am out on the hills every day now, in pursuit of the old Principle. He still is elusive tho ubiquitous. But I take a grab here and a grab there, and make him yield up a fragment of a secret each day. Yesterday, while trying to catch him by means of sandpaper, I had an exhilarating struggle with him. I was literally limp at the end of it, but came out of it with what I think is a solid drawing.

In the mornings I make jelly, and in the afternoon I battle with hills. In the evenings I usually get roped into a lamp-light drawing.

But as for wishing to be sure that things could flow unhampered from me at any time—I must confess this is not what I desire.

I love the struggle—I like the feeling of bringing forth my aesthetic offspring, perfect, if possible, and with a feeling of triumph in the end. No, it would take much for me to be willing to part with the struggle, the painful groping, the eternal Search!

Drawing from your unique point of view

There is a tree outside my window with a trunk like a cadence. That sounds quite silly, but it really isn't. I have been drawing and painting this tree a great deal lately— in combination with other things of course. It's a strange tree. It appears very awkward at first glance, but becomes graceful as soon as one learns how to look at it.

It is an apple tree and there is another besides it, which remains awkward no matter how you look at it. It squirms all over the landscape, and there is a consistency in its squirming. So I have drawn that also.

Loving the subject of what you make

Probably the best drawing I did all summer was one I did on sandpaper of my studio with an old apple tree in the foreground.

This tree was my obsession of the summer. I doubt whether any person or thing has ever had a greater hold on me than that tree did and still has….

I never could see and still deride the idea expressed in novels and movies, of an artist never being able to do something great until he has met his ideal, his inspiration! But this tree has had a very definite influence on me.

I have existed as an artist before, and will be able to hereafter without it—but while I was with it, I was given an ever-varying aesthetic treat. My studio looked right out upon it. There it stood, stark and yet infinitely graceful, bare and still full of something greater than mere life. It had the dignity, the purity of line of a beautiful antique. Its battered look heightened this appearance, for it was not the destruction of a sudden storm or of any accident. It was the slow steady seasoning and mellowing of years and years. Time and the elements had gradually stripped it of all inessentials and left a magnificent, awe-inspiring essence of a tree.

This tree, as most, and probably all, other objects do, had the fault of changing its character. Some days it was slender, almost prettily graceful. Other days it seemed stocky and sturdy, like the veteran New Englander that it was. Sometimes it had an almost sinister aspect, for one of its branches ended in a sort of claw-like formation.

Not only that, but the surrounding foliage and the sky fell into varying arrangements because of it. I never tired of drawing and painting it…it is only once in a while that even a tree can achieve such perfection. My tree stood out frankly bleak and bare, but with a personality, which made it the center of everything.

In fact, it always had that faculty. All else around it was only an accompaniment, a set of variations to its big Beethoven-like theme.

Creating to understand

Just now I am wrangling with hills. In looking at a peaceful, rolling hillside one would never guess that it could be composed of such a disturbing collection of planes.

The trouble is that each integrant part insists on living a perspective-life all its own …and it's the very devil to reconcile all these seemingly conflicting fragments to the big.

I am determined once and for all to get at the bottom of the principle which governs all of this. It's the same thing I encountered in the squashes last fall. I thought that I caught a glimpse of them, and seemed on the verge of grasping it. But I see now, I was far from it.

Within the last few days it has seemed as though I were again hot upon its trail, and that I could catch it by the tail at the next turn. Then, given a mighty strength for a mighty effort, I could drag the beautiful beast out into the open, where I could look upon it with fierce analytical gaze!

It's an exciting hunt. My aesthetic existence teems with forms which project themselves tauntingly toward me, recede elusively from me, bulge, flow, and most of all, turn triumphantly over the edge of things, leaving one to wonder what's going on beyond.

But of course that's exactly the place where I can't afford to give up, so girding my aesthetic loins (used in figurative sense only!) and setting my face in dogged ecstasy, I go at 'em again!

Well, it's fun anyway.

Learning to organize your mind through composition

There are some who accuse nature of being without finality. I have, up to yesterday, agreed theoretically to that-although in reality my reactions have been like this:

In the last few years everything about me has seemed so compellingly ordered that merely looking at a spot has brought a composition popping out at me.

I could just draw anything these days. Before the period, which I have just de-scribed, it was often necessary for me to search out a satisfying composition. Sometimes I couldn't find a thing in places which, if I saw them now, would pursue me with their beauty of line, and inter-relation of forms.

I am wondering—has nature always been completely harmonious, and was it a lack in myself which prevented me from perceiving it—or is nature a casual, haphazard affair, upon which we impose rhythms, and then proceed to portray a harmony which really exists only in ourselves?

Is our power of organization superior to that of God-or is it vice-versa?

Since last night's dream—(egotist tho I am)—I leave the laurels to God!

Whether the universe is built up on a visible harmony, or an imperceptible order, or an infinite disorder—I'll take it just as it is, thank you. There is enough diversity in it for each artist to take what he wants, and yet enough viewpoints left for everyone who follows.

And it has an inexhaustible supply of springboards!

Getting super specific in your work

Of course I could not tell whether I had managed to get across as much as I wanted in it, but at least while I was doing it I felt as tho I were getting closer than usual to what I had so often tried for. This was the flatness of the earth, the upstandingness of objects, the inter-relation of forms, and even a hint of a big rhythm.

Book illustration's all right—I'm in a strong position there, luckily, and can do just about what I please, and of course it's what I'm living on-but what I like to do best of all is to make myself receptive to the rhythm and forms about me and to record them in as intense yet logical a way as I am capable of.

Treating yourself as a work of art

Just as I am interested in covering a piece of paper with interesting lines and proportions and pleasing combinations of color, so I am interested in making a decoration of myself. And more than a decoration. My body is the piece of paper, so to speak, and aside from arranging interesting colors and masses upon it, l also am impelled to make them express the collection of things which are myself.

One's drawings should be so sincere and individual as to be worthy of one's signature but to require none. One's person should be worthy of the same signature, and I would like to look so much like myself, that people seeing me would say, as they sometimes do of some of my pictures, "that is unmistakably 'Wanda Gág'"

imagine her dresses are extraneous to her self-expression.

Is it the dancer in me which is responsible for this desire to be decorative, to be an aesthetically moving thing? Or is it that terrific urge which I always have, of wishing to be a complete unit—of leading an integrated existence?

At any rate, whether it be to my discredit or not, I enjoy having clothes which express myself. I am not interested in being "well-dressed" in the conventional sense, but I do enjoy looking "just right." I enjoy pleasing others in this way. I also appreciate it when others accomplish the same thing. I have often wondered how it was possible for artists, who were so very sensitive in their reactions to art, to make such a dowdy mess of their own ensemble without being offended by it.

Defining your own theories about art

I tried to explain to him, as I have tried before, what I was trying to do with the atmosphere around objects…To me, sometimes, an object projects repetitions of its own form into the surrounding atmosphere, and in this way space achieves a three dimensional quality. But this is not all, and what I am going to attempt to explain now is much harder to put one's finger on. It is that any point in space represents a potential part of a plane or point in perspective.

As I go around or sit and think and look, I am aware not only of the volume, but also of the potential form of the atmosphere about me.

I am still as deeply absorbed in the form of the atmosphere around objects as I was several years ago and I have tried this and that way of expressing this feeling. But it is elusive and abstruse. I think in a drawing of Yucca lilies and squash leaves, which I did this summer, I may have approached it, but not as completely as I wished.

I can think of various tricks by which I could achieve it in a superficial way, but in this I am not at all interested. I want to show the volume of atmosphere, its essential form as related to (or rather produced by) the object it surrounds. Furthermore, there is the inter-relation of these atmosphere forms and rhythms as created by the interrelation of a group of several objects. Well, it's all very difficult, but it's pretty definite in my perceptions. For instance in drawing an interior, I am not only interested in drawing objects which are conversing as to form and weight—the cubical character of a trunk, the squareness of tables, the cylindrical quality of a lamp chimney, the flatness of walls, the spherical quality of fruit, the discs of flowers, etc.

I will call them positive forms. But what about all the negative forms which are produced by the presence of these several objects?

And just because an exciting volume of space is, well let's say not tactile-should it be ignored and considered empty? There is, to me, no such thing as an empty place in the universe—-and if Nature abhors a vacuum, so do I-and 1 am just as eager as nature to fill a vacuum with something—if with nothing else, at least with a tiny rhythm of its own, that is a rhythm created by its surrounding forms.

Of course the forces in these negative spaces can make things very complicated for a poor finite artist. The cubical space I tried so hard to illustrate is a very simple problem. But take an apple, a candle, a box, and a bunch of flowers. Think of what odd elusive negative forms are created in such a case, and anything might happen when you allow all these enveloping layers of concrete space to interact upon each other. A group of objects looked at in this way has the possibility of producing anything from extreme chaos to a complete and faultless symphony.

My attitude toward this is not soulful, or abstract—if it were, some tricks I know of would express the problem very neatly and glamorously. It is my extremely physical reaction to a space which makes it so difficult. When a space can be as definite, as surely invested with volume and character as a tangible object—what is one going to do about it?

Well, as long as this problem remains unconquered to me, I can lack for no incentive to go on with the search instead of doing the same things over and over again.

Now maybe this self-projection can go on until everything is jammed together or possibly these space projections go on and on, overlapping and getting all mixed up with each other. But this does not concern me at present. I merely wish to harmoniously rev-ordinate [sic] these and in order to do this I must stop their force-lines or masses at a point which is most advantageous to my symphony. For instance in a piece of music, the repetition of an e may be just the thing—at the same time you are repeating several other notes, but there comes a time when you don't want the e anymore. You could let it go on, but it would mess up your harmony—so you stop it at the point you see fit, and allow one of the other notes to encroach upon the sound space left by the removal of the e-sound.

So, at certain points I find it necessary to stop the projections of certain objects sooner than that of others, and sometimes an object is denied any projection at all. It is just allowed enough space to exist in as is—its lines or masses are not forceful or important enough to bear repetition. That valuable space which so many people consider empty is needed for other things!

Moving through creative blocks and fears

Earle, dear heart, it is for such a reason that I wish so much that you would just say a stern "no" to some of the distractions which you allow to swerve you, and to sit down and write and write and write. You are dear to me for many things, but we can never be as close as we are capable of being until you give me the joy of sharing in your creation. I have often told you that it is nothing to me whether you succeed or not. It would not matter if everything you wrote were turned down. You have plenty to say and I believe you could find a way to say it. Whenever I try to talk to you about this, you are bothered and you say it troubles you constantly. But I know that without being told and what is the use of allowing yourself to be tyrannized by such a feeling?

The thing to do is to get rid of the feeling and the only way to get rid of the feeling is to start doing something—anything—not "in the fall, in the winter," "when this is done or that has happened." There are always things happening and hampering one, and if one were to wait for the end of those hampering happenings, one would never be able to start anything. I know all sorts of things cut into your life, but it would make me so happy if you could ignore them a little more. By ignoring I mean do them if necessary, but do them somewhat indifferently, reserving your real energy for writing.

Rhythm

Perhaps I worship rhythm as some worship the sun, a god, or the body…there seems to be a great marching of things, a mighty moving along of forces to measures which can only be felt at certain moments.

All about me there is a glorious fitting together of things, round, smooth faces with corresponding sockets; sharp painful angles with their complementary shapes; long vivid jags into crevices that hold them perfectly and calmly, so to restore the equanimity and rightness of things; and most of all perhaps, long tendrilly jutterings-out to receive and organize all the helpless fringes and frayed edges of our groping lives.

There is, to me, no such thing as an empty place in the universe—and if nature abhors a vacuum, so do I—and I am just as eager as nature to fill a vacuum with something—if with nothing else, at least with a tiny rhythm of its own, that is rhythm created by the surrounding forms.

Perspective

To me, perspective is more than a mechanical set of rules—I see in it the potentialities for rhythmic forcefulness and even emotional significance. With form and space it is the same: a still life is never still to me, it is solidified energy —and space does not impress me as being empty. So far I have not been able to objectify these theories to my satisfaction and I think it possible that through the structural use of color I may gain some ground here.

Living a life outside of art

Since I have been spending the greater part of my summers in Connecticut, this feeling of back to nature has been gradually growing upon me. To run around barefooted or with sandals only, to wear only one article of clothing, to dash over hills with hair flying, to putter around in a garden, to paint and draw such fragments of the great rhythm, which are granted to me, and to have treetops under the open sky—all this has gradually become to me the nicest way of living.

Her Books

Author and illustrator:

Batiking at Home: a Handbook for Beginners (Coward McCann, 1926)

Millions of Cats (Coward McCann, 1928): online read aloud

The Funny Thing (Coward McCann, 1929): online read aloud

Snippy and Snappy (Coward McCann, 1931): online read aloud

The ABC Bunny (Coward McCann, 1933): online read aloud

Gone is Gone; or, the Story of a Man Who Wanted to Do Housework (Coward McCann, 1935)

Growing Pains: Diaries and Drawings for the Years 1908–1917 (Coward McCann, 1940)

Nothing At All (Coward McCann, 1941): online read aloud

Translator and illustrator:

Tales from Grimm (Coward McCann, 1936)

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (Coward McCann, 1938)

Three Gay Tales from Grimm (Coward McCann, 1943)

More Tales from Grimm (Coward McCann, 1947)

Illustrator only:

A Child’s Book of Folk-Lore—Mechanics of Written English, by Jean Sherwood Rankin (Augsburg, 1917)

The Oak by the Waters of Rowan, by Spencer Kellogg Jr (Aries Press, New York, 1927)

The Day of Doom, by Michael Wigglesworth (Spiral Press, 1929)

Pond Image and Other Poems, by Johan Egilsrud (Lund Press, Minneapolis, 1943)

Translator only:

The Six Swans, illustrations by Margot Tomes (Coward, McCann & Geoghegan, 1974)

Wanda Gág's Jorinda and Joringel, illustrations by Margot Tomes (Putnam, 1978)

Wanda Gag's the Sorcerer's Apprentice illustrations by Margot Tomes (Putnam, 1979)

Wanda Gag's The Earth Gnome, illustrations by Margot Tomes (Putnam, 1985)

The Sweet Porridge, illustrations by Jill McDonald [et al.] (Methuen Educational, 1966)

Bibliography:

Note: The words highlighted in pink include the stuff I don’t have access to yet but want to read eventually.

Articles

“In Tribute to Wanda Gág” Horn Magazine

These Modern Women: A Hotbed of Feminists” by Wanda Gag (The Nation 1927)

"Art for Life’s Sake," by Anne Carroll Moore. In Horn Book Magazine, vol. 23, no. 3 (May-June 1947).

Books

Wanda Gag : A Catalogue Raisonne of the Prints — this book tells a detailed story of her life with an emphasis on her print work

Girlhood diary of Wanda Gág, 1908-1909: Portrait of a Young Artist — this book…

Growing Pains (her autobiography)

The Story of an Artist, by Alma Scott

The Gag Family, German-Bohemian Artists in America, by Julie L’Enfant

Wanda Gág: The Girl Who Lived to Draw, by Deborah Kogan Ray

Wanda Gág: Storybook Artist, by Gwenyth Swain

Wanda Gág: A Life of Art and Stories, by Karen Nelson Hoyle

Videos

Wanda Gág: A Minnesota Childhood: a great 20 min video bio that paints a picture of her childhood and provides an overview of her career.

![1928 INSIDE OUT. [STUDY FOR CHRISTMAS AT TUMBLE TIMBERS.] 1928.jpeg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/633642065c54c64149dbe183/1716060062847-GD7PYSBHQO6G4DQKJZAE/1928+INSIDE+OUT.+%5BSTUDY+FOR+CHRISTMAS+AT+TUMBLE+TIMBERS.%5D+1928.jpeg)